“I made history, didn’t I?” Kevin McCarthy was saying Tuesday night, a few hours after he in fact did, by becoming the first speaker of the House to ever be ousted from the job. History comes at you fast—and then it hurtles on. By yesterday morning, the race to replace him was fully in motion, even as the wooden Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy sign still hung outside his old office.

Washington loves a death watch, which is what McCarthy’s speakership provided from its first wee hours. He always had a strong short-timer aura about him. The gavel looked like a toy hammer in McCarthy’s hands, the way he held it up to show all of his friends when he was elected. He essentially gave his tormentors the weapon of his own demise: the ability of a single member of his conference to execute a “motion to vacate” at any time. Tuesday, as it turned out, is when the hammer fell: day 269 of Kevin held hostage.

McCarthy tried to put on a brave face during Tuesday’s roll call. But he mostly looked dazed as the bad votes came in, sitting cross-legged and staring at the ground through the back-and-forth of floor speeches, some in support, some in derision.

“This Republican majority has exceeded all expectations,” asserted Elise Stefanik of New York, cueing up an easy rejoinder from McCarthy’s chief scourge, Matt Gaetz of Florida: “If this House of Representatives has exceeded all expectations, then we definitely need higher expectations!”

Garret Graves of Louisiana hailed McCarthy as “the greatest speaker in modern history,” which brought an immediate hail of laughter from the minority side. Otherwise, Democrats were content to say little and follow the James Carville credo of “When your opponent is drowning, throw the son of a bitch an anvil.”

Mike Garcia of California urged his fellow Republicans to be “the no-drama option for America,” which did not seem to be going well. Andy Biggs of Arizona concluded, “This body is entrenched in a suboptimal path.”

By 5 p.m., that path had led to a 216–210 vote against McCarthy—and the shortest tenure of a House speaker since Michael C. Kerr of Indiana died of tuberculosis, in 1876.

How should history remember McCarthy’s speakership? Besides briefly? McCarthy was never much of an ideological warrior, a firebrand, or a big-ideas or verdict-of-history guy. He tended to scoff at suggestions of higher powers or lofty purposes.

Insomuch as McCarthy had any animating principle at all, it was always fully consistent with the prevailing local religion: self-perpetuation. Doing whatever was necessary to hang on for another day. Making whatever alliances he needed to. Could McCarthy be transactional at times? Well, yes, and welcome to Washington.

The tricky part is, if you’re constantly trying to placate an unruly coalition, it’s hard to know who your allies are, or when new enemies might reveal themselves. That became more apparent with every “yea” vote to oust McCarthy—Ken Buck of Colorado, Nancy Mace of South Carolina. At various points, McCarthy had considered those Republicans to be “friends.” And “you can never have too many friends,” McCarthy was always telling people. In the end, he could have used more.

“Kevin is a friend,” Marjorie Taylor Greene was saying outside the Capitol before Tuesday’s vote. She turned out to be steadfast. Reporters surrounded Greene like she was an old sage. “Matt is my friend,” Greene also said, referring to Gaetz. George Santos walked by behind the MTG press scrum, and three of the Greene reporters trailed after him. Lauren Boebert—whom Greene had once called a “little bitch” on the House floor (not a friend!)—followed Santos. Boebert wound up supporting McCarthy, sort of. “No, for now,” she said when her name came up in the voice vote.

McCarthy always tried to convey the impression that he was having fun in his job, and was aggressively unbothered by critics who dismissed him as a lightweight backslapper, in contrast to his predecessors, Paul Ryan the “policy” guy and John Boehner the “institutionalist.” Back in April 2021, I was sitting with McCarthy, then the House minority leader, at an ice-cream parlor in his hometown of Bakersfield, California. He used to come in here—a place called Dewar’s—for Monday-night milkshakes after his high-school football practices. He kept saying hello to people he recognized and posing for photos with old friends who stopped by our table. At one point that night, McCarthy turned to me and indicated that being someone people wanted to meet was one of the main rewards of his job.

He was always something of a political fanboy at heart, hitting Super Bowls and Hollywood awards parties. He liked meeting celebrities. He showed me pictures on his phone of himself with Kobe Bryant, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Donald Trump. We had just eaten dinner at an Italian restaurant, Frugatti’s, which featured a signature dish named in his honor—Kevin’s Chicken Parmesan Pizza. (He had ordered a pasta bolognese.)

“I know the day I leave this job, the day I am not the leader anymore, people are not going to laugh at my jokes,” McCarthy told me then. “They’re not going to be excited to see me, and I know that.” This was something to savor, for as long as it lasted. And that basically became the game: take as many pictures and gather as many keepsakes as he could to prove the trip was real.

“Keep dancing” became a favorite McCarthy mantra during his abbreviated time with the speaker’s gavel—as in, keep dancing out of the way of whatever “existential threat” to his authority came along next. McCarthy would contort himself in whatever direction was called for: promise this to get through the debt-ceiling fight, finesse that to keep the government open, zig with the zealots, zag with the moderates. Renege on deals, if need be; throw some bones; do an impeachment; order more pizza.

“Tonight, I want to talk directly to the American people,” McCarthy said on the morning of January 7. After being debased through 15 rounds of votes, he could finally deliver his “victory” speech as the newly (barely) elected speaker of the House. As a practical matter, it was after 1:15 a.m., and the American people were asleep. Everything about McCarthy’s big moment felt like an overgrown kid playacting. There he was with a souvenir hammer, after near-fisticuffs broke out between two of the crankier kids at the sleepover.

McCarthy would grab whatever sliver of a bully pulpit he could manage. “I never thought we’d get up here,” he said as he began his late-night acceptance speech. Immediately, everyone wondered how long he could possibly stay. And how it would end. This seemed to include McCarthy himself. “It just reminds me of what my father always told me,” he said. “It’s not how you start. It’s how you finish.”

McCarthy had moved into the speaker’s chambers a few days earlier, before it was officially his to move into. Why wait? He took a picture with his freshly engraved nameplate on the door. He invited his lieutenants over to check out his new office. Not bad for a kid from Bakersfield! He ordered more pizza. And Five Guys. Dancing requires fuel.

But throughout his tenure, McCarthy carried himself with a kind of desperate edge, which his critics sensed and held against him. “We need a speaker who will fight for something, anything, besides just staying or becoming speaker,” Bob Good of Virginia said in a floor speech on Tuesday.

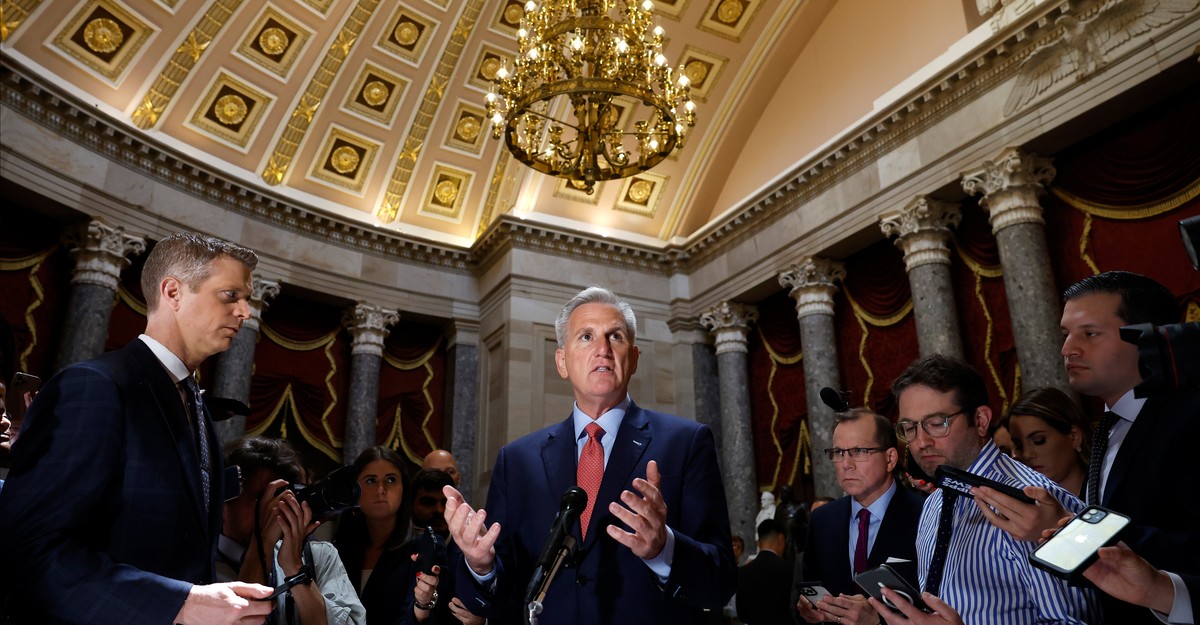

This was late in the afternoon, when everyone still expected McCarthy to keep fighting. His supporters viewed his defeat as temporary. Gaetz stepped out onto the Capitol steps and was quickly engulfed by a scrum of boom mics, light poles, and onrushing reporters. Back inside, McCarthy grabbed the last word on the crazy spectacle.

“Judge me by my enemies,” the now–former speaker said, maybe trying to sound defiant.